LSD, lawsuits and anarchy – it’s no wonder the group are still so prolific

This year, the Grateful Dead celebrate their 50th anniversary, a milestone marked by a slew of releases – the first of which is an imminent double-album compilation – and a Dead documentary produced by Martin Scorsese. The band haven’t actually been in existence since the death of Jerry Garcia in 1995 – a passing marked by the half-mast hoisting of a tie-dyed Dead flag on the San Francisco city hall flagpole – though its spirit has been sustained by an extended community of Deadhead fans, served by the ongoing issue of live albums of vintage performances.

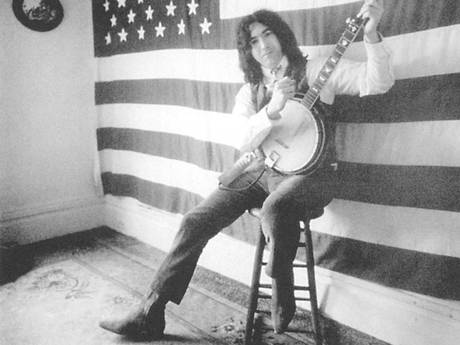

Formed in 1965 from jug-band roots, the Dead were a unique mix of psychedelic rock, rootsy Americana (before the term was coined) and avant-garde experimentalism, whose long, freeform extemporisations came to exemplify the San Francisco sound in the first flush of Haight-Ashbury hippiedom. Jerry Garcia was a banjo-picking bluegrass fan turned lead guitarist, while at the opposite pole, bassist Phil Lesh was a classically trained aficionado of the avant-garde, full of bizarre ideas. Alongside Lesh and Garcia were the young pop-rocker Bobby “Ace” Weir and blues singer/organist Ron “Pigpen” McKernan, their freewheeling collusions riding the polyrhythmic momentum provided by drummers Bill Kreutzmann and Mickey Hart.

The Dead’s earliest claim to fame was as the house band for Ken Kesey and the Merry Pranksters’ prototype hippie happenings – Kesey associate Ken Babb regarded them as “the engine driving the Pranksters’ spaceship”. These happenings, in turn, led to the “Acid Tests” staged on the West Coast, at which all participants, band and audience alike, were dosed with LSD. The Dead had unlimited access to this powerful new mind-altering drug, as the legendary drug chemist Owsley Stanley III (aka “the Bear”) also happened to be their chief soundman. Not only did he make the world’s purest acid, he would also build the band the world’s best sound system – a massive wall of speakers custom designed to fill arenas with sound.

Grateful Dead formed in 1965 from jug-band roots (Rex Features)

Though Garcia was the group’s guiding spirit, it was run on collectivist lines, with each member of the extended Dead family, from musicians to road crew and administrators, receiving the same $25 per week in the band’s early years. Warner Bros Records executive Joe Smith despaired of their deliberately anarchic collectivism: when meetings were called, around 60 people would show up to negotiate, including mothers nursing babies and probably a dog or two.

The Dead’s family spirit also spread to their fanbase, and created a broader sense of community. Whereas other artists clamped down on bootleggers, the Dead encouraged them, setting aside areas at concerts where tapers could set up microphones for optimum sound. The band realised that this mini industry, rather than chipping away at their own income, sustained and spread their appeal.

Their lack of worldliness led to some disastrous business choices, however, such as the decision to make a movie which all but bankrupted the band; or the legendary visit to play at the Egyptian pyramids, the costs for which were to be recouped by a live triple-album that had to be abandoned due to the out-of-tune piano which was the result of an earlier cheapskate short-term decision. For a ha’porth of tar, their ship all but sank.

Things were not helped, in the early years, by their inability to handle the discipline of studio recording: as an improvising band, they found it hard to distil their music into album-sized portions. Faced with the disappointing performance of their debut LP, they chose to dig an even deeper hole with the follow-up, Anthem of the Sun. The band racked up an unprecedented $100,000 in studio costs while they painstakingly spliced fragments of live shows, studio takes, drum solos, and recordings of natural sound into collaged suites.

The band haven’t actually been in existence since the death of Jerry Garcia in 1995 (Rex Features)

Though flawed, Anthem of the Sun remains one of their most thrilling albums, as confirmed by the appalled reaction of Warners’ Smith, who considered it “the most unreasonable project with which we have ever involved ourselves” – a back-handed testimonial which the band proudly brandished as proof of their alternative attitude.

Salvation came in the form of Live Dead, a double album that played to the band’s performance strengths, and afforded the room for the serpentine peregrinations of tracks such as the 25-minute “Dark Star”. Live Dead became a fan favourite, establishing the strategy of interspersing studio releases with generous live offerings, such as the Europe ’72 live triple-album.

The Dead finally came of age as a studio band with the 1970 double-whammy of Workingman’s Dead and American Beauty, a pair of back-to-their-roots folk-rock outings inspired by Crosby, Stills & Nash and The Band, which secured them their first Top-30 placings and remain their most immediately approachable albums. The latter, especially, is a gorgeous piece of work, which finds the band nailing vocal harmonies in a way that they’d never managed before.

In 1973, they set up their own record labels – Round Records and Grateful Dead Records – for subsequent releases, the first of which was Wake of the Flood. The album went Top-20, but it was the merchandising innovations on the accompanying promotional concert tour which had more lasting significance. Fans were encouraged to sign up to the Dead’s mailing list, which by 1975 numbered around 80,000, and enabled the band to sell tickets and T-shirts directly to their fanbase. Within a few years, they had become the world’s most successful (ostensibly) anarchist company.

Through the Eighties, their shows grew in popularity and their coffers overflowed accordingly. Forbes magazine rated them among the top 30 highest-paid entertainers of 1989, with an estimated annual income of $12.5m (£8.1m), and by 1991, they were the world’s highest-grossing tour act, playing to an astonishing 1.6 million fans that year. Their merchandising arm expanded to incorporate comics, ties, backpacks, dolls and golf and skiing equipment, while the ice cream manufacturer Ben & Jerry’s was forced to cough up a slice of the proceeds of its Cherry Garcia flavour. (Initially bluffing that they’d stop production, the owners soon changed their mind after realising it was their biggest seller.)

While the band’s druggy reputation is by no means over-exaggerated, not all of the profits went up their noses. A portion has been channelled into the Rex Foundation, a charitable fund set up in 1983 which so far has given more than $8m to around 1,000 diverse recipients, including the American Indian College Fund, the Lithuanian Basketball Team and the Zen Hospice Project.

Since Garcia’s death halted the group’s progress in 1995, the remaining members have performed both solo, and in various aggregations as the Other Ones, Rhythm Devils, and Furthur (the latter a reference to the Merry Pranksters’ bus). And this July, Weir, Lesh, Hart and Kreutzmann will reunite for three shows in Chicago, with Phish’s Trey Anastasio deputising for Garcia.

In 1998, the Dead were recognised in the Guinness Book of Records as having played the most rock concerts (2,318), to more people (an estimated 25 million), than any other act. Not bad going for a bunch of old hippies.

‘The Best of the Grateful Dead’ is released on 30 March on Rhino Records’

Source: independent.co.uk

Let us know what you think by commenting below! Sign In or Post as a Guest.

Latest posts by PsychRock Staff (see all)

- Pastel Jazz Goth Artist BRYSON CONE Releases Debut Album! - March 4, 2020

- JOEL VANDROOGENBROECK, Belgian Experimental Music Pioneer & Founder Of Legendary Krautrock Band BRAINTICKET, Passes Away At The Age Of 81 - January 8, 2020

- ALAN DAVEY Forms The First HAWKWIND Supergroup HAWKESTREL - August 5, 2019