On the eve of the release of his photographic autobiography, guitarist Jimmy Page reflects on “the multifaceted gem that is Led Zeppelin”.

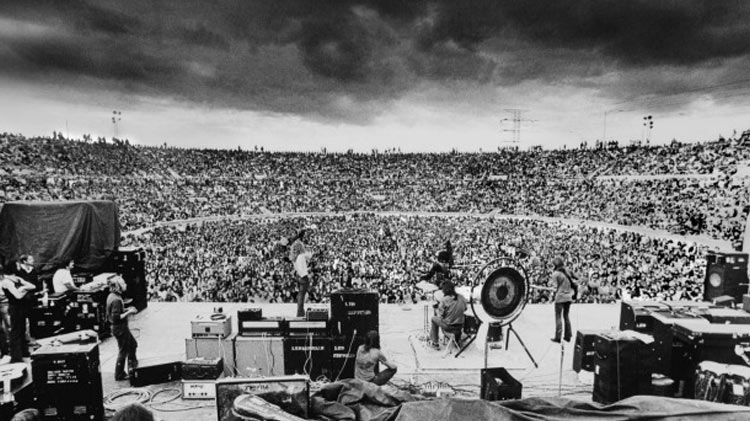

Melbourne, February 20, 1972. In the skies above a sold-out Kooyong Stadium, a mighty storm is brewing. The wind is ruffling the golden mane of singer Robert Plant as he stands, hand in pocket, microphone to his lips. Drummer John Bonham and bass player John Paul Jones are hunching their shoulders against the weather. Jimmy Page, guitarist, band leader, is poised centre stage with his instrument slung low and his right arm flung high, pointing to the heavens as if he has just peeled off the mother of all riffs and summoned this giant black thundercloud. At the bottom of the picture, stamped on an amp case in capital letters: “LED ZEPPELIN LONDON”.

“Dramatic, isn’t it?” Page leans over Jimmy Page, the coffee-table tome he calls his “photographic autobiography” and checks out his 28-year-old self. “I’d shaved off my beard by the time we played Sydney,” he says, flicking to another photo. “At the press conference, no one knew who I was for ages.” Now 70, whippet thin and white-ponytailed in a black outfit topped with a wispy black scarf, rock music’s greatest living guitar hero has just welcomed me into an antique-festooned drawing room in the Gore Hotel in Kensington, central London, looking every inch the lord of the manor.

“Australia!” he says after he’s shaken my hand with the same fine-boned fingers that created that arpeggiated, finger-picked chord progression on Stairway to Heaven, then sprawls lankily on a red velvet couch. “Led Zeppelin only went there once. I remember it was very censored. There were little black squares over all the nipples in Playboy.”

Ramble on: Led Zeppelin on stage in the Netherlands, in 1980. Photo: Getty Images

He laughs, his dark eyes crinkling at the corners. A bookish only child, a loner who devoted long stretches of time to mastering the guitar, Page claims he’s always had good recall. But as he set about sifting through the thousands of images he’d amassed on jpegs, in archives and in photo albums retrieved from his mother’s house, his memory was jogged time and again.

“If you get a point of reference then you find straight away that you have an anecdote around it,” he says in his clipped Home Counties tones. “You remember what the furniture was like in the room, or what you were doing and who you were doing it with or wha’ever.”

Not that Jimmy Page spills any beans. Which is kind of the idea. “I was always being asked to write a book but they always wanted the salacious, kiss’n’tell stuff and I wasn’t prepared to do that.” He shrugs his slim shoulders. “I knew I had photos going right back to when I was a kid, so I thought it might be interesting and challenging to do a book this way.”

A reformed Led Zeppelin in full flight at Shepparton Studios, 2007. Photo: NewSouth Books

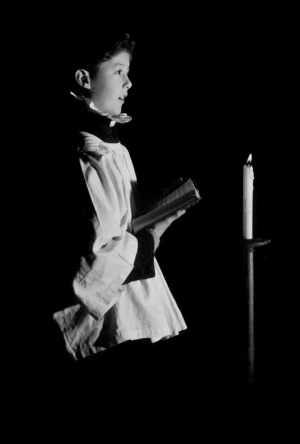

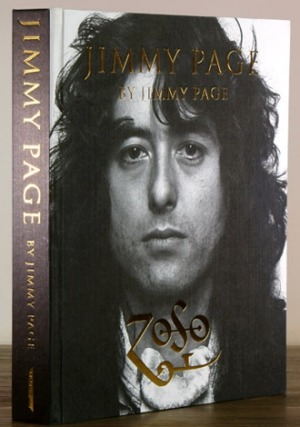

Packed with photos Page has arranged chronologically, captioned accordingly and supplemented with tour schedules, passport stamps and memorabilia, the book – an affordable reissue of a limited edition of 2500 copies that sold out in 2010 – is both a document of a changing Britain and a sanctioned take on the life in music of an icon. There he is as a 13-year-old choirboy in a candlelit church near his childhood home in Epsom, Surrey. There, with his first electric guitar, sliding across the stage on his knees in an after-school gig. And there, with some of the bands he graced in the ’60s as the hottest young guitar slinger in town.

There he is playing duel guitar alongside Jeff Beck in the Yardbirds, dressed like a Byronesque dandy and scraping a cello bow across his Fender Telecaster. There he is – and there, and there again – with Led Zeppelin, the band he founded in 1968. The awesome foursome. The quartet of master musicians who conquered the world with a mix of blues, folk and sledgehammer rock before imploding in 1980 following the death of John Bonham at Page’s Berkshire home. As dangerous as they were spiritual, with a reputation for excess and otherworldly dabblings and a sound that touched both the soul and punched you in the guts, Led Zep hypnotised a generation. With over 300 million records sold, they remain one of the biggest rock bands in the world.

What a confessional Jimmy Page might have been. The under-age groupies. The heroin years. The spooky goings-on at Boleskine House, the mansion on the shores of Loch Ness in the Scottish Highlands that once belonged to 19th century libertine and occultist Aleister Crowley, the “most wicked man in Britain”, and which Page owned from 1970 until 1992.

Page from the cover shoot for his only solo album, 1988’s Outlander. Photo: NewSouth Books

It could have told the story, finally, of Page’s personal ZoSo symbol, as seen on the cover of the band’s untitled fourth album in 1971 and stitched onto the velvet suits with the Chinese dragons and astrological signs that Page wore onstage at the time. A glyph that suggests all kinds of dark magick, adding to the mystique stoked by Led Zep’s larger-than-life manager Peter Grant, who cannily refused to let the group release singles or appear on television. Page has always refused to explain ZoSo. The symbol is there on the menu of his website, jimmypage.com. It is here, too, on the cover of the book in front of us, emblazoned in a swirling gold font under a portrait of Page taken in 1977, on Led Zeppelin’s private tour plane. “It is what it is,” says Page of ZoSo. “People know me by it. I’m not going to pronounce it, or dissect it. It is part of that incarnation in Led Zeppelin.”

Led Zeppelin: for the 34 years since the group disbanded, Page has been the main keeper of the flame. Remastering the catalogue. Releasing posthumous DVDs and live albums. Accepting gongs such as 2012’s Kennedy Award for Lifetime Contribution to the Arts, as bestowed by President Obama at the White House (“Obama told me he and Michelle had listened to Led Zeppelin at college”).

Stairway to heaven: Page as a 13-year-old choirboy. Photo: NewSouth Books

The critics hated them at first, especially in America. But Led Zep’s priapic power chords and howled vocals, their Middle Earth references and soft melancholia, lassoed the Zeitgeist. They became a cult – a religion – regardless. Of the nine albums the band released, the first six, from Led Zeppelin to Physical Graffiti, are acknowledged as among the best hard-rock albums ever made. And Jimmy Page – OBE, honorary doctor of music, inductee into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame – produced them all, experimenting with guitar approaches and recording techniques along the way.

Led Zeppelin were arguably past their creative peak by the time of their split: Page had become a heroin addict; Bonham had sunk into the chronic alcoholism that killed him. A grief-stricken Page initially refused to pick up a guitar. When he did, it was for the short-term collaborations, soundtrack work and guest appearances that have marked his career ever since.

Page in London, in June 2014. Photo: Getty Images

His CV from back then reads like a who’s who of British ’60s artists, including the Who, the Kinks, Them, Tom Jones, Donovan, Lulu, Dusty Springfield, Herman’s Hermits and the Rolling Stones (who launched their album Beggars Banquet with a custard-pie fight here at the Gore Hotel in 1968). “My tastes as a teenager were already so varied,” says Page. “I listened to classical guitar. Indian music. Arabic music. Rockabilly. Elvis. The Chicago blues movement, which was just so creative.

“I could play some harmonica, too, and suddenly here was this young guy who could do all this stuff.” He pauses, sips his coffee. “I was always asking questions of engineers, learning about recording techniques, microphone placement, stuff like that. Learning to read music. Learning, learning, learning.” When, tired of playing in other people’s bands, Page put his foot on the fuzz pedal and joined electric-blues band the Yardbirds in 1966, he went in with a grab bag of ideas, directions he then explored and developed in his live improvisations as the band’s solo lead guitarist (after Eric Clapton had left and Jeff Beck was sacked). Then he took these “colours and textures” into Led Zeppelin and examined them even further.

Jimmy Page, the photographic autobiography. Photo: Supplied

Not that there is any evidence of their legendary on-tour shenanigans in Jimmy Page. No reference to the infamous groupie and mud shark incident in Seattle in 1969 (Bonham); or the Hilton hotel room that was totalled by a samurai sword in 1971 (Bonham); or the reputed two-groupies-in-a-bath with four live octopuses in Pasadena in 1969 (Page); or any snaps of the 14-year-old schoolgirl and love interest, Lori Maddox, allegedly hidden in various hotel rooms in 1971 and 1972 (Page).

Indeed, aside from a photo of Page backstage in Indianapolis, swigging from a bottle of whisky, there is nothing in Jimmy Page to suggest that life on the road was anything other than a succession of Boy’s Own larks and a lot of cigarette smoking. He still smokes, sometimes. “Don’t recoil in horror,” he quips, misinterpreting my body language. “But clearly I’m not in a situation now where I need to be recovering from too much alcohol or whatever. I gave that all up years ago.” When? “I had young children, and I thought, ‘This is totally …’ ” He changes track. “I do not want my children to have memories of me being drunk and loud and argumentative or whatever,” he says, and I wonder if the use of the word “whatever” is a veiled reference to heroin, a habit he reportedly kicked in the early 1980s. “The younger family are all teenagers now, so it has been a while.”

Page divorced his third wife, Jimena Gomez-Paratcha, with whom he has done extensive charity work for children in Brazil, in 2008. So does he have a new partner? He stares at me from the other end of the couch. “Ah, no,” he says eventually. “No. Since my separation from the last one I have actually really valued my freedom.”

Good for you, I say. “But I do have friends.” He smiles, raises his eyebrows.

I still can’t help picturing Page, the loner, the self-confessed “peculiar, unusual boy”, rattling about in The Tower House, the extravagant neo-Gothic home in nearby Holland Park he bought from the actor Richard Harris in 1972 (outbidding David Bowie), just after Led Zeppelin returned from their only tour of Australia. Reputedly haunted, with murals painted on its ceiling and mediaeval-style fantasy fireplaces, the many rooms of The Tower House accommodate works from Page’s extensive collection of Pre-Raphaelite art, just as they do all the Led Zep-related material he’s amassed over the years – the guitars and the stage clothes, the lanyards and the tour programs and the photos. “I can’t really throw anything away, can I?” he says good-naturedly. “I can’t put anything in the dustbin, cos all of a sudden you find them for sale on eBay.”

Get a furnace, I suggest. “Yeah.” A smile. “Stoking the fire in the basement with a pitchfork and a pair of horns on.”

Page’s interest in the occult has long been the subject of speculation. In early interviews he mentioned his interest in Aleister Crowley, the self-styled “Great Beast” who’d bought Boleskine House to conduct black magic experiments intended to coax out the forces of evil, and whose maxim was “Do what thou wilt shall be the whole of the law”. Religious groups duly concluded that Page worshipped Satan. People began playing Led Zeppelin’s records backwards to try to uncover fiendish messages.

Page bought Crowley’s old estate in early 1970 but ended up spending just six weeks there, more because of the increasing success of Led Zep than any of the alleged poltergeisty goings-on in the property. In 1976 he recorded one of the fantasy sequences for the now cult Led Zeppelin concert film The Song Remains the Same (each personalised segment offering an insight into a band member’s personality) on the hillside behind Boleskine House.

“We put in the fantasy sequences because we ran out of concert footage,” says Page, who is seen as a pilgrim climbing the mountain, a symbol of his search for enlightenment, and reaching out to touch The Hermit, the adept, the loner, only to discover that The Hermit is himself.After which he whizzes back to the womb again. “So it’s me going up and up towards this beacon of truth and figure of knowledge.” He flings his right arm high. “And then having this epiphany that truth can come to you at any point in your life. Which is what I’d like to think for everybody, you know?” There’s more behind it. Magic. Spirituality. Secrets he’s keeping. “I wanted people to think, ‘What is that? What’s he getting at?’ ” Page flashes a smile. “There you go,” he says. “A bit more mystery for you.”

Source: smh.com.au

Let us know what you think by commenting below! Sign In or Post as a Guest.