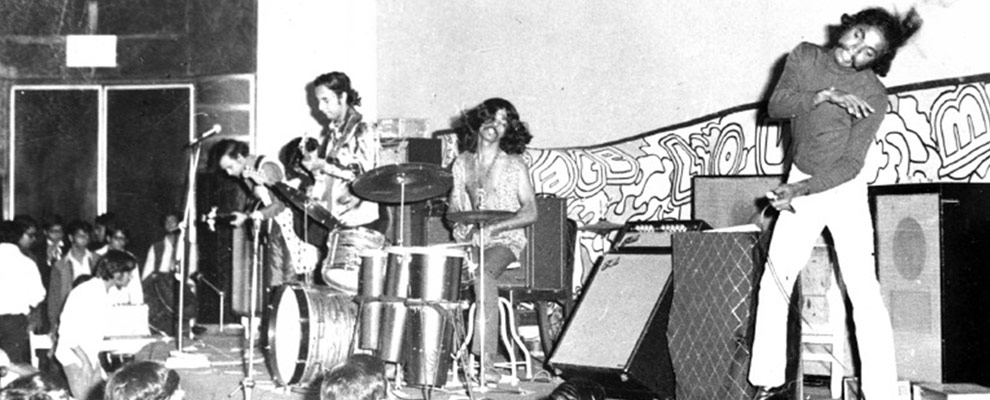

Combustibles at the Eros cinema in Mumbai in the early seventies. Courtesy Sidharth Bhatia

For many Westerners, the words “India” and “rock” remain synonymous with a particular location: Rishikesh. It was there, famously, in the foothills of the Himalayas, that The Beatles learnt transcendental meditation with Maharishi Mahesh Yogi in February 1968.

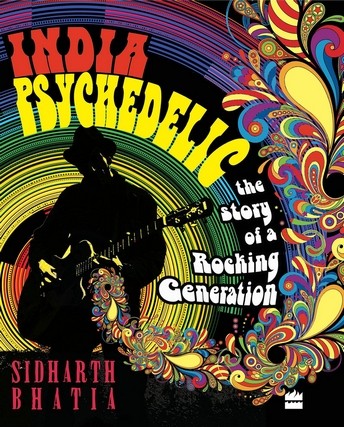

George Harrison also studied sitar with Ravi Shankar while in Rishikesh, but Sidharth Bhatia’s book looks at how Western pop and rock influenced India, rather than vice versa. India Psychedelic is, at root, a love letter to the Indian rock bands who embraced the “devil’s music” from the early 1960s onwards. They tuned crackling short-wave radios to the subversive-seeming sounds of Radio Ceylon, and learnt songs by The Rolling Stones et al from cherished records randomly imported by outsiders.

In so doing, bands such as Kolkata’s Great Bear and Mumbai’s Velvette Fog rebelled against the prevailing mores of Mother India, a country still in denial about its emerging youth culture. Transitional period, cabaret-type singers such as Chic Chocolate and Chennai’s Ernest Ignatius, the Anglo-Indian who sang I Married A Female Wrestler, were one thing, but Indian rock ’n’ roll’s raucous riposte to innocuous, if colourful, Hindi film scores and Carnatic and Hindustani music – ie Indian classical music – dealt the shock of the new.

Even in 1974, when The Illustrated Weekly of India put the country’s best known psychedelic rock act Atomic Forest on its cover, the accompanying headline was the work of scaremongers: “Attitudes of Indian Youth Today: Down with God, Country, Parents, Everything.”

Bhatia is a veteran, Mumbai-based print and television journalist of 35 years’ standing. In his opening chapters, he sketches the challenging sociopolitical backdrop from which Indian rock and pop emerged. “The swinging 60s that swept Britain and the West in general barely trickled in here,” he writes. “India was too busy trying to survive.”

The country fought three wars between 1962 and 1971, and was shaken by famine. The 1973 oil shock, which resulted in India’s oil-import bill tripling, led to an energy crisis. In such a climate, the Simla Beat Contest – an annual draw for young rock and pop bands from all over India – must have seemed a sweet distraction.

The author records how the Mumbai-based talent competition, staged by the Imperial Tobacco Company to promote Simla cigarettes, was integral to the growth of Indian rock music; the epicentre towards which all early aspirants gravitated.

The Shanmukhananda Hall-staged event would kick-off at the decidedly non-rock ’n’ roll hour of 10am, and participants – The Beethovens, The Psychos, The Combustibles, etc – would typically perform on rudimentary, often home-made equipment. Electric-guitar pickups were fashioned from radio-set components, and amps tended to be the crude sort used at political rallies, rather than the purpose-built Marshalls and Fenders enjoyed in the West.

Any attendant rock ’n’ roll gigging culture, Bhatia explains, was slow to emerge. Initially, Indian bands in Mumbai had to play the same staid restaurants and hotels as the jazz acts and crooners they were gradually displacing. In the more liberal and cosmopolitan climate of 1960s Kolkata, however, a certain decadence distinguished Park Street, a thoroughfare that the author describes as a “lost arcadia”.

It was in the city in 1965 that the early events management company Bandwagon offered punters the chance to dance exotic new dances such as the Shish Kebab, while The Gaylads and The Debonairs rocked-out. Junior Statesman magazine – despite its stuffy title, its enthused youth culture reportage was just as key to the growth of Indian pop as the Simla Beat contest – soon ran a piece advising girls how to wear their saris while shaking a leg. For all their potency, almost all of the early bands relied on cover versions. In 1960s India, rock ’n’ roll was a spectacularly new language, mostly for learning rather than rewriting. The country’s dearth of recording studios and companies also meant there was no overarching music business as such; no easily accessed conduit of communication, bar the stage.

Consequently, the few raw-but-sparky recordings made by India’s rock and pop pioneers are now valuable artefacts. India Psychedelic flags up a copy of The Savages’ 1973 album Black Scorpio, which sold for US$3,000 (Dh11,019) on eBay in 2011, and collectors also prize Simla Beat 70 and Simla Beat 71, rare LP recordings of the competition’s finalists in those two years.

As his book progresses, Bhatia shows how the output of Indian rockers reacted to new directions taken by their Western contemporaries. In the late 1960s, as communist Naxal groups gained traction across India, and “elite colleges such as St Stephens in Delhi hummed with leftist activity”, the American protest-singer movement led by Bob Dylan inspired Indian songwriters such as Susmit Bose to comment on their own country’s affairs. Bose also sang a Hindi translation of We Shall Overcome for Indian prime minister Indira Gandhi.

Though Bhatia spoke with scores of Indian rock musicians for India Psychedelic, their quotes are often disappointingly insipid. This is a forgivable pitfall, perhaps, of interviewing musicians unused to the press about things that happened decades ago, but the book’s tendency to repeat nuggets of information is more irksome, and sometimes feels like an attempt to pad out its 153 pages.

Bhatia is good, though, on Biddu, the Bangalore-born singer and producer who made it in the West after writing Carl Douglas’s 1974 hit Kung Fu Fighting (which went on to sell 11 million copies), and on Asha Puthli, the glamorous, Mumbai-born bohemian and sometime Andy Warhol associate whose music was eventually sampled by rappers Jay Z and 50 Cent.

In his acknowledgements section, the author explains how India Psychedelic grew out of an earlier magazine piece he wrote for Time Out Mumbai about an impromptu gig that Led Zeppelin’s Robert Plant and Jimmy Page played in Mumbai in October 1972, and his revisiting of that topic here is fascinating.

Elsewhere, though, there are frustrating omissions; tricks missed. Bhatia reports that one of his interviewees, Arvid Jayal, a former member of Delhi rock group Hypnotic Eye, performed for The Beatles while they were staying at Maharishi Mahesh Yogi’s ashram. Strange, then, that no account of what happened that momentous day is given.

James McNair writes for Mojo magazine and The Independent.

Source: thenational.ae

Latest posts by PsychRock Staff (see all)

- Pastel Jazz Goth Artist BRYSON CONE Releases Debut Album! - March 4, 2020

- JOEL VANDROOGENBROECK, Belgian Experimental Music Pioneer & Founder Of Legendary Krautrock Band BRAINTICKET, Passes Away At The Age Of 81 - January 8, 2020

- ALAN DAVEY Forms The First HAWKWIND Supergroup HAWKESTREL - August 5, 2019